Food inflation and agribusiness

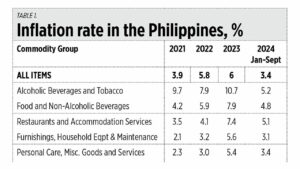

Last week, the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) reported the country’s inflation rate for September 2024 and it was low at 1.9% compared to the 6.1% in September 2023. Good news indeed. See the following related reports in BusinessWorld: “Inflation falls below 2% for first time in over four years” (Oct. 4), “Inflation surprise backs Philippine […]

Last week, the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) reported the country’s inflation rate for September 2024 and it was low at 1.9% compared to the 6.1% in September 2023. Good news indeed. See the following related reports in BusinessWorld: “Inflation falls below 2% for first time in over four years” (Oct. 4), “Inflation surprise backs Philippine central banker’s easing plan” (Oct. 4), “Slowing inflation gives Philippine central bank room for more cuts” (Oct. 7).

Food inflation in particular dropped to only 1.4% in September 2024 vs. 9.7% in September 2023. The January-September 2024 overall inflation and food inflation were down to only 3.4% and 4.8%, respectively (see Table 1).

With the declining inflation rate, and a declining interest rate to follow, I see household consumption (which comprises 75% of GDP) to grow around 5.5% to 6% in the second half (H2) of 2024 from 4.6% in H1 of the year. This will pull up overall GDP growth to around 6.6% in H2 of 2024 from 6.2% in H1.

AGRICULTURE BUDGET AND GROWTH

The budget of the Department of Agriculture (DA) is big and rising fast, from P78 billion in 2020 to P114 billion this year and a proposed P129 billion next year (all nominal values). The DA has had double digit yearly growth from 2022 to 2025 and possibly beyond. But the yearly growth in nominal values of Agriculture, Fishery and Forestry (AFF) is only in the single digits (see Table 2).

Somehow there is a disconnect between government’s agriculture spending and actual agriculture performance. It is possible that the bulk of the DA budget is spent on salaries, meetings, and travel and less is spent on the actual needs of the farmers.

PRIVATE AGRIBUSINESS AND SELF-RELIANT AGRICULTURE

My friend and batchmate from the UP School of Economics batch 1984, Leo Riingen, founder and president of the IT school Informatics, went into agribusiness both as a hobby and as an economic project to help expand food production in the country. He owns several hectares of land in Pampanga which are planted with fruit trees like lanzones and mangos, and sweet corn (not rice), and where he raises livestock like goats, horses, pigs, and chickens. There is also a tilapia fishpond.

Being an urbanite and having entered agribusiness rather late, he said that he went through “expensive, funny, trial and error farming.” Among his experiences and lessons — aside from the fact that farming is hard (he tried planting 200 lanzones trees and after the 10th tree he left the work to his farmhands — that he can share are the following:

1. Agritech is important. There are too many uncontrollable variables in the way of a good harvest. Calamities, insects, soil quality, and even freak small tornadoes spoiled his anticipated harvest.

2. Do not overly trust “experienced” farmers. Science is still the most reliable adviser, and this includes YouTube clips by experienced and successful farmers abroad. He trusted his farmhand who told him 10,000 tilapia fingerlings would be best for his pond. He ended up feeding 10,000 tilapias for months only to be told he needed to harvest and sell them quickly as they were getting older and he had only a few fishing rods.

3. Agri insurance is needed to help protect farmers. He was happy when his sow gave birth to 14 piglets. Then in a few weeks all the piglets died, as did their mom, from foot and mouth disease. Then 10 chickens ready to be fried the following week were hit by avian flu and all died.

4. Solar power is a heaven-sent invention for farmers. He adapted to the last dry spell with solar powered pumps to draw water from deep wells — there was no need to beg for irrigation from the government. He spent P200,000 for the solar set up with no battery, he then built irrigation canals, and the system is able to irrigate up to four hectares of land.

You are doing very well, Leo. Contributing to higher food production via the use of modern technology is a low-key but high-impact economic project.

DAR AND AGRIBUSINESS UNCERTAINTY

The government’s land reform program should have ended in 1998 because the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP) law of 1988 had a timeline of 10 years. Then the program was extended for another 10 years, and extended again, and now there is no more deadline. The Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) has become a “forever” bureaucracy with a “forever” budget and powers of intervention that distortion and create business uncertainty — successful agribusiness projects with large pieces of land can still be subject to forced land redistribution.

I wish the DAR and the endless land redistribution program would shut down and end. The agrarian reform programs of Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and other Asian nations were short and swift. Once the original timeline was reached, forced land redistribution should end. All land transfers would then be done via market transactions, not political coercion.

Bienvenido S. Oplas, Jr. is the president of Bienvenido S. Oplas, Jr. Research Consultancy Services, and Minimal Government Thinkers. He is an international fellow of the Tholos Foundation.