Interest rate cuts and credit ratings upgrade

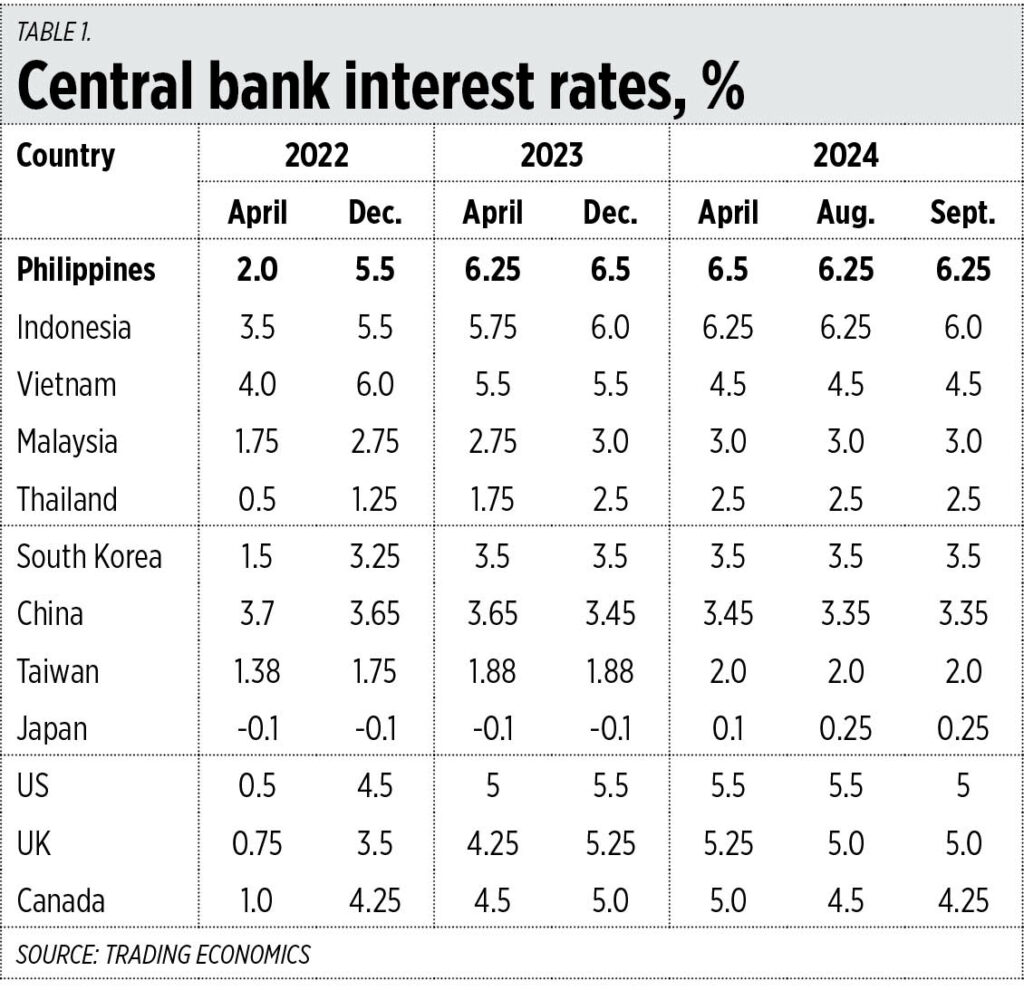

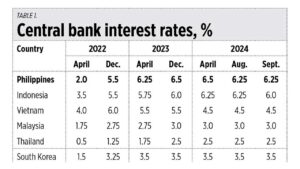

Among the important events that happened over the last few weeks was the big interest rate cuts in the US and Canada, with the Philippines, Indonesia and few other countries following with smaller interest rate cuts. In Asia, the Philippines had, until the second quarter this year, the highest interest rate set by monetary authorities […]

Among the important events that happened over the last few weeks was the big interest rate cuts in the US and Canada, with the Philippines, Indonesia and few other countries following with smaller interest rate cuts.

In Asia, the Philippines had, until the second quarter this year, the highest interest rate set by monetary authorities or central banks at 6.5%. Despite this policy, which was supposedly to control high inflation, the Philippines endured the highest inflation rate in the ASEAN-6 in 2023 at 6%, and the second highest in the region from January to July 2024 at 3.7%, next to Vietnam’s 4.1%.

So it was good that the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) finally realized that its high interest rate policy should be reversed even if at a piecemeal rate.

Meanwhile, Japan raised its interest rate from -0.1% to 0.25% (see Table 1).

I bumped into the president of Meralco PowerGen Corp. (MGen), also the former president of Aboitiz Power Corp., Manny Rubio. He has a bright finance mind because two big conglomerates have trusted him. I asked Manny about the huge recent US Fed rate cut and its microeconomic impact to households, he replied that “Broadly it signals that the government is less worried now about controlling inflation and is now prepared to shift to an expansionary policy. For companies with substantial funding requirements to support their capex plans and new projects, this would mean a substantial reduction in their funding costs. Such savings would allow energy companies to complete new generation capacities and distribution facilities more cheaply which would eventually reduce the cost of electricity for the consumers.”

In a Viber message, Budget Secretary Amenah F. Pangandaman welcomed the interest rate cuts of the US Fed and BSP, saying, “this will have significant reduction in our interest payment which is now a significant share of our total annual budget. And this will eventually lead to efficient budget allocation to sectors that need more funding and help expand our economy.”

Secretary Pangandaman’s concern is correct because the amount of our interest payments has been rising fast, from P361 billion in 2019 to P429 billion in 2021, P503 billion in 2022, P628 billion in 2023, and P457 billion already in January-July 2024 alone. If this trend continues, then the full year 2024 interest payment will rise to P783 billion. Or a doubling of our interest payment in just five years from 2019 to 2024.

ROADMAP TO CREDIT RATINGS

There were a number of recent pieces in BusinessWorld on the subject of credit ratings: “Recto says Philippines still on track to achieve ‘A’ credit rating” (June 10), “Philippines needs 6-7% growth to achieve ‘A’ credit rating — Recto” (Aug. 14), “R&I upgrades PHL credit rating to ‘A-’” (Aug. 15), “Public-finance roadmap to help elevate PHL to ‘A’ credit rating — Budget dep’t” (Sept. 17), “Philippine credit rating upgrade possible if GDP grows faster than expected” (Sept. 18). There was also yesterday’s column, Introspective, entitled “Philippine sovereign credit rating: An ‘A’ rating, how soon?” (Sept. 23) by Alex Escucha.

My column has also discussed this subject previously: “Declining borrowings and improving credit ratings” (June 18), “Fast growth towards better credit ratings” (Aug. 13), “MUP pension reform and ‘A’ credit ratings” (Aug. 20).

Finance Secretary Ralph G. Recto and Budget Secretary Pangandaman’s desire for the Philippines to attain a credit rating of “A” is understandable. An “A” means our capacity to service our loan obligations is high, so the cost of borrowing, both public and corporate, will be lower. And financing important projects like infrastructure will entail lower costs.

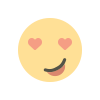

Currently, the Philippines has credit rating of BBB+ “stable” under S&P, Baa2 “stable” under Moody’s, and BBB “stable” under Fitch. Then there are the ratings of BBB+ “positive” from R&I, and A- “stable” from the Japan Credit Rating Agency (JCR). An A- from the JCR is good but it is the Big Three — S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch — that matter most.

One thing I notice though is that high credit ratings can also lead to the problem of a “moral hazard” in economics. Since the cost of borrowing is low due to high ratings, there is a tendency by governments to over-spend and over-borrow. So, the high ratings do not lead to less public debt and lower Debt/GDP ratios, the reverse can happen. This is happening in the G7 industrial countries and other countries around the world.

For example, there is Canada which has had a high AAA “stable” rating for decades and its Debt/GDP ratio kept rising, from 76% in 2003 to 107% in 2023. The US, the UK, France, Japan, and Italy all suffered declines in ratings over the past two decades but still at high A levels, except Italy (see Table 2).

An upgrade in ratings to “A” is important. But more important is how we can control our spending, deficit, and borrowings in years where there are no economic or finance crises, like 2022 to the present. We should have a budget surplus, not a deficit; we should reduce, not increase, our public debt stock; and we should reduce, not maintain, our Debt/GDP ratio.

Bienvenido S. Oplas, Jr. is the president of Bienvenido S. Oplas, Jr. Research Consultancy Services, and Minimal Government Thinkers. He is an international fellow of the Tholos Foundation.